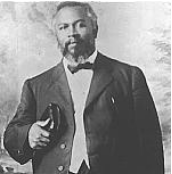

William Joseph Seymour, later affectionately known as “Daddy” Seymour (May 2, 1870 – September 28, 1922), was an African American minister whom, at the turn of the twentieth century, God used to helped facilitate the Azusa Street revival.

Seymour was born the son of freed slaves in Centerville, Louisiana. Fleeing the poverty and oppression of life in southern Louisiana, Seymour left his Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and other states, often working as a waiter in home in early adulthood. He traveled and worked in big city hotels. In Indianapolis, Seymour was converted in a Methodist Church; however, he soon joined the Church of God Reformation movement in Anderson, Indiana. While with this conservative Holiness group, Seymour acknowledged the call to preach, but it wasn’t until a nearly fatal bout with smallpox that left him scarred in his face and blind in one eye that he yielded to the call.

Attending a Bible school founded by Charles Parham, he learned the major tenets of the Holiness Movement and accepted the belief in glossolalia (speaking in unknown tongues) as a confirmation of the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Because of the strict segregation laws of the times, Seymour was forced to sit outside the classroom in the hallway; however, he did not receive the Holy Spirit baptism with the evidence of speaking in tongues. He was later appointed to minister in a church in Los Angeles, though, as a consequence of his Pentecostal doctrine, they locked him out of the building, and he was removed from the parish to which he had been appointed.

Moving into the home of Edward Lee, janitor of a local bank, he began ministry with a prayer group that had been meeting regularly in a local home. As the group sought God for revival, their hunger intensified.

Finally, on April 9, Lee was baptized in the Holy Spirit with the evidence of speaking in other tongues. When the news of his baptism was shared with the true believers, a powerful outpouring followed. Many received the Holy Spirit baptism as Pentecostal revival surged. That evening would be hard to describe. People fell to the floor as if unconscious, others wept as they prayed aloud, still others shouted. One neighbor, Jennie Evans Moore, played the piano, although she never had any training. Over the next few days of continuous outpouring, hundreds gathered. The streets were filled, and Seymour preached from the prayer group’s porch. On April 12, three days after the initial outpouring, Seymour received his baptism of power.

Seymour rejected the existing racial barriers, as was customary (and legally enforced in some areas of that day), in favor of “unity in Christ”. This revival meeting extended from 1906 until 1909, and became the subject of intense investigation by more mainstream Protestants. The resulting movement became widely known as “Pentecostalism”, likening it to the manifestations of the Holy Spirit recorded as occurring in the second chapter of Acts.

REVIVAL COMES FROM HEAVEN WHEN HEROIC SOULS ENTER THE CONFLICT DETERMINED TO WIN OR DIE-OR IF NEED BE, TO WIN AND DIE! “THE KINGDOM OF HEAVEN SUFFERETH VIOLENCE, AND THE VIOLENT TAKE IT BY FORCE.”

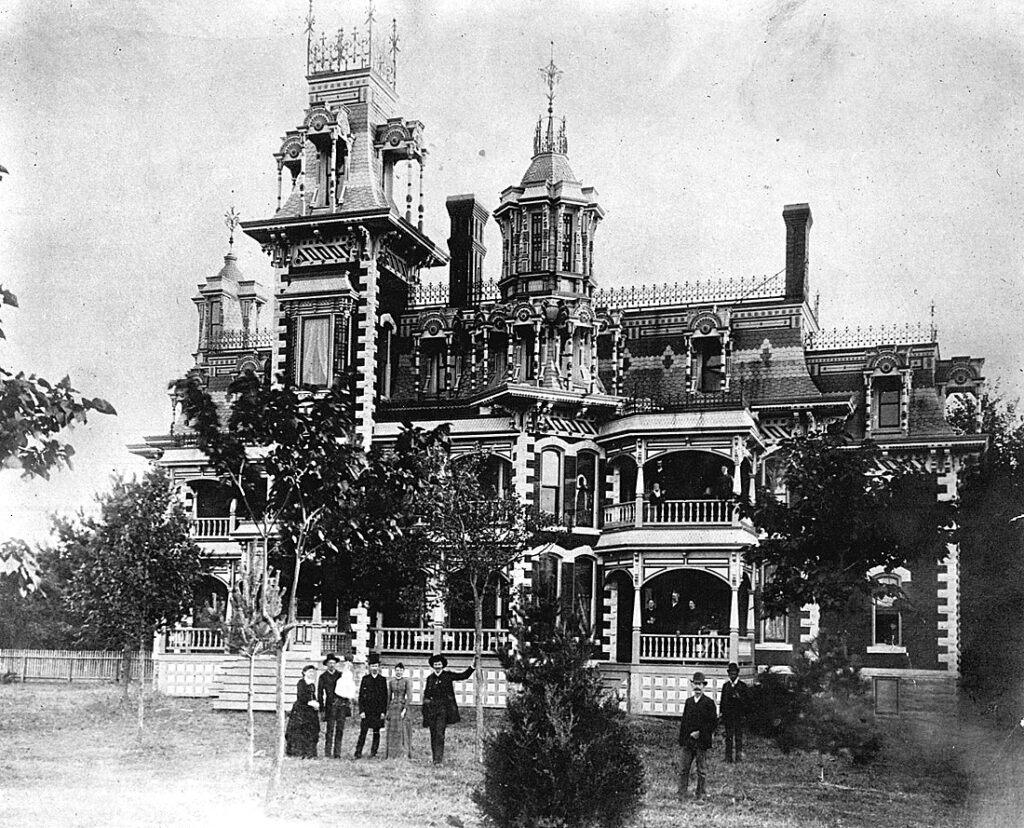

CHARLES FINNEY

While there had been similar manifestations in the past (the Cane Ridge, Kentucky revival a century before in the Second Great Awakening being one such example), the current worldwide Pentecostal and charismatic movements are generally agreed to have been in part outgrowths of Seymour’s ministry and the Azusa Street Revival. Quickly outgrowing the prayer group’s home, the faithful searched for a home for the new church. They found their building at 312 Azusa Street. The mission had been built as an African Methodist Episcopal Church, but when the former tenants vacated, the upstairs sanctuary had been converted into apartments. The downstairs became the home of the Apostolic Faith Mission. Mismatched chairs and wooden planks were collected for seats and a prayer altar, and two wooden crates covered by a cheap cloth became the pulpit.

On April 17, The Los Angeles Daily Times sent a reporter to the revival. In his article the next day, he lampooned the meeting and the pastor, calling the worshippers “a new sect of fanatics”, and Seymour “an old exhorter.” He mocked their glossolalia as “a weird babel of tongues.” More important than the critical opinions expressed by the reporter was the providential timing of his visit. The article was published on the same day as the great earthquake in San Francisco. Southern Californians, already gripped with fear, learned of a revival where doomsday prophecies were common.

Immediately, Frank Bartleman, an itinerate evangelist, and Azusa Street participant published a tract about the earthquake. Thousands of the tracts, filled with end-time prophecies, were distributed. Soon, multitudes gathered at Azusa Street. One attendee said more than a thousand at a time would crowd onto the property. Hundreds would fill the little building; others would watch from the boardwalk; and, more would overflow into the dirt street. With the help of a stenographer and editor, the mission began to publish a newspaper, The Apostolic Faith. Seymour’s sermons were transcribed and printed, along with news of the meetings and the many missionaries that were being sent out. The papers literally spread the Pentecostal message across the globe. Circulation for the little paper passed 50,000.

Services at the mission were conducted three times each day at 10 AM, Noon and 7 PM, although often they ran together until the entire day became one worship service. This schedule was continued seven days a week for more than three years. It was common for the lost to be saved, sick healed, demonized delivered, and seekers to be baptized in the Spirit than in any other year of America’s history, Seymour led an interracial worship service. At Azusa Street there were no preferences for age, gender, or race. One worshipper said, “The blood of Jesus washed the color line away.”

Despite all of the so-called “success”, the revival faced opposition from without and within. Charles Parham, insulted by the racial composition of the meetings and emotionalism brought the first major split, though many others followed. Two ladies of the dissenters took the main mailing lists, crippling The Apostolic Faith newspaper. Not many years after the revival began only a skeleton crew, mostly black and mostly the old prayer group, kept the fire burning in the old mission.

On September 28, 1922, Seymour experienced chest pains and shortness of breath. Although a doctor was called, his last words were “I love my Jesus so.” Seymour was laid to rest in Los Angeles’ Evergreen Cemetery. His gravestone simply reads, “Our Pastor”.